1xBet CI – Paris en ligne en Côte d’Ivoire

Parmi les opérateurs sportifs en ligne, 1xbet.com est l’un des plus populaires et des plus réussis. Le bookmaker est bien connu dans de nombreux pays du monde, y compris en Côte d’Ivoire. Le site officiel en Afrique de l’Ouest est également connu sous le nom de 1xbet.ci et est l’un des opérateurs sportifs les plus populaires. Paris sportifs légaux et sécurisés, cotes très compétitives pour les événements avant-match et en direct, diverses options de paris et de nombreuses promotions avantageuses – voilà ce que propose la société de paris 1xBet aux joueurs d’Abidjan et d’autres villes de Côte d’Ivoire.

Parmi les opérateurs sportifs en ligne, 1xbet.com est l’un des plus populaires et des plus réussis. Le bookmaker est bien connu dans de nombreux pays du monde, y compris en Côte d’Ivoire. Le site officiel en Afrique de l’Ouest est également connu sous le nom de 1xbet.ci et est l’un des opérateurs sportifs les plus populaires. Paris sportifs légaux et sécurisés, cotes très compétitives pour les événements avant-match et en direct, diverses options de paris et de nombreuses promotions avantageuses – voilà ce que propose la société de paris 1xBet aux joueurs d’Abidjan et d’autres villes de Côte d’Ivoire.

| 📕 Nom du Bookmaker | 1xbet.ci |

| 📆 Année de Création de l’Entreprise | 2007 |

| 🌐 Adresse du Site Web Officiel | www.1xbet.ci |

| 💰 Bonus de Bienvenue | 100 % sur le premier dépôt (bonus jusqu’à 60 000 XOF) |

| 💳 Montant Minimum du Dépôt | 200 XOF |

| 💸 Montant Minimum du Retrait | 500 XOF |

| 🏆 Services Offerts | Paris sportifs et esport, paris en direct, poker en ligne, jeux de machines à sous, casino en direct, loteries |

| 📱 Application Mobile | Disponible pour Android et iOS |

| 📞 Canaux de Support Client | E-mail, Numéro de Hotline, Chat en Ligne, Formulaire de Commentaires |

L’opérateur en ligne propose plusieurs méthodes d’inscription au choix, et après l’inscription, les clients ont accès à l’ensemble des services et produits de 1x bet, y compris l’accès aux jeux de casino en ligne. Le site du bookmaker propose différentes versions linguistiques, dont le français, permettant aux utilisateurs de profiter des produits de l’entreprise dans leur langue préférée. La société de paris figure parmi les meilleurs bookmakers sur le marché international et garantit un niveau de service élevé. Dans l’article suivant, nous discuterons plus en détail de la manière de devenir client de l’opérateur 1x bet et de placer des paris réussis.

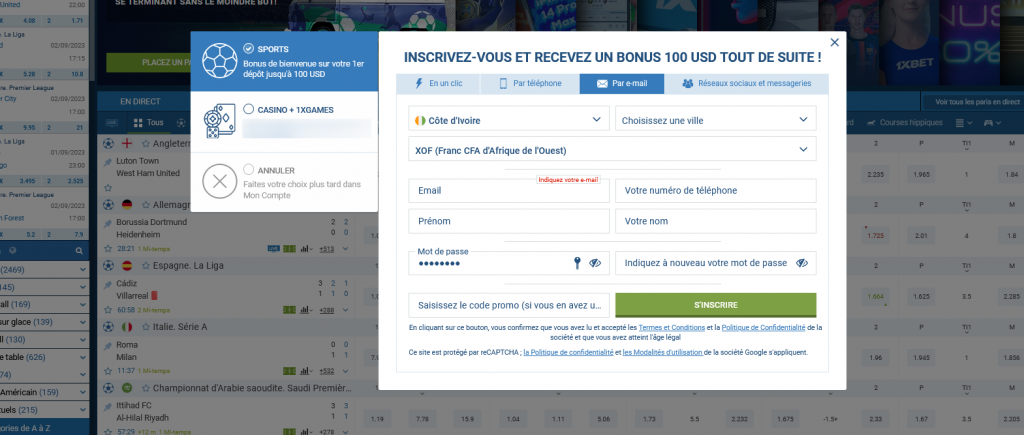

1xBet Inscription en Côte d’Ivoire en 1 clic

Il existe plusieurs options de formulaire d’inscription pour créer un compte 1xBet et commencer à placer des paris sportifs sur le site. La méthode la plus courante et la plus simple consiste à créer un compte en un seul clic. Que faut-il pour cela ? Le joueur doit fournir les informations suivantes :

- Pays de résidence de l’utilisateur ;

- Devise pour la gestion du compte de jeu ;

- Code promotionnel actuel.

Comment créer un compte avec un numéro de téléphone ?

Les joueurs qui préfèrent également placer des paris depuis leurs smartphones choisissent souvent de devenir clients de l’opérateur en ligne 1x bet en utilisant leur téléphone mobile. Pour ce faire, vous devez effectuer les actions suivantes :

- Appuyer sur le bouton « Inscription » et choisir cette méthode de création de profil ;

- Entrer le numéro de téléphone ;

- Insérer le code de vérification qui sera envoyé par l’opérateur sur le mobile sous forme de SMS ;

- Choisir la devise préférée ;

- Insérer, le cas échéant, le bon de promotion dans le champ correspondant.

En enregistrant le formulaire, le joueur accepte la politique de confidentialité de l’entreprise et les conditions d’utilisation. La création d’un compte atteste également que le joueur est majeur. Lors du processus de vérification, l’opérateur peut découvrir que l’utilisateur est mineur, ce qui entraînerait le blocage du compte du joueur.

S’inscrire sur 1xBet CI par email

En choisissant l’option d’inscription par courrier électronique, l’utilisateur passe par une procédure complète pour ouvrir un compte et un compte de jeu. Ensuite, il n’est pas nécessaire de perdre du temps à remplir des onglets dans le compte personnel qui contiennent les informations personnelles du client de l’entreprise. Ainsi, vous pouvez créer un compte par e-mail de la manière suivante :

Choisir le pays de résidence, la ville, et la devise préférée ;

- Fournir une adresse e-mail personnelle et un numéro de mobile ;

- Entrer le nom et le prénom du joueur ;

- Choisir un mot de passe pour l’accès futur au compte personnel et le saisir à nouveau ;

- Insérer le code promo 1xBet si le joueur en possède un.

Créer un compte via les réseaux sociaux

Une manière très pratique de devenir un client enregistré auprès de la société de paris sportifs est de s’inscrire à l’aide d’un compte sur les réseaux sociaux. Lors du choix de cette option, le système présente les réseaux sociaux et messageries populaires disponibles pour la liaison. Que devez-vous faire ? Le joueur doit effectuer les actions suivantes :

- Choisir le réseau social préféré ;

- Confirmer la duplication des informations personnelles ;

- Indiquer la devise préférée pour les opérations ;

- Activer le code bonus si disponible.

L’authentification sur le site est une étape essentielle pour accéder à votre compte personnel. Pour effectuer un 1xBet Login, il vous suffit de cliquer sur le bouton « Connexion » situé en haut à droite de la page d’accueil.

Bonus de bienvenue de 1xBet Cote d’Ivoire sur le premier dépôt

Dans le cadre du programme de fidélité 2024, le principal opérateur sportif offre un bonus de bienvenue aux nouveaux arrivants. Juste après l’inscription, chaque nouveau client du bookmaker a la chance de recevoir un bonus de 100 % sur son premier dépôt.

Le nouveau client de 1×bet après son inscription et son dépôt peut bénéficier d’un bonus pouvant aller jusqu’à 60 000 XOF pour les paris sportifs !

Le montant minimum de rechargement du compte doit commencer à partir de 1 euro. La société de paris accorde en retour un bonus de 100 % du dépôt, dont le montant maximum peut atteindre 100 euros. Il est également important que l’utilisateur ait fourni toutes les informations personnelles manquantes dans son compte personnel pour recevoir le bonus de bienvenue. Pour jouer les fonds bonus, il suffit de suivre les règles de l’offre :

- Composer des paris combinés d’au moins trois matchs ;

- Les cotes des matchs sélectionnés doivent être d’au moins 1,4 ;

- Miser le bonus cinq fois.

La période de validité du bonus de bienvenue du club de bookmakers 1xBet est de trente jours. Il est également important que les paris sur les totaux et les handicaps, ainsi que les paris avec remboursement, ne seront pas pris en compte pour le décompte du bonus.

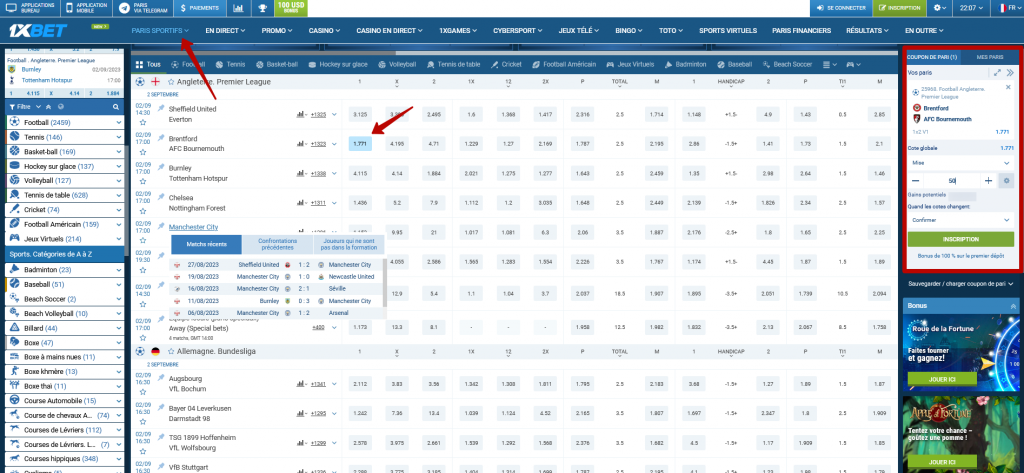

Comment faire des paris sportifs dans une agence de bookmakers en ligne ?

Contrairement à de nombreux autres bookmakers, la société leader 1×bet ne limite pas ses clients aux offres proposées sur les principaux domaines sportifs. Chaque jour, le site de l’opérateur propose plus de 20 000 paris sportifs dans plus de cinquante disciplines sportives à travers le monde. Les clients de l’agence ont donc l’embarras du choix, que ce soient des fans de football, de hockey et de basket-ball, ou des passionnés de disciplines plus rares.

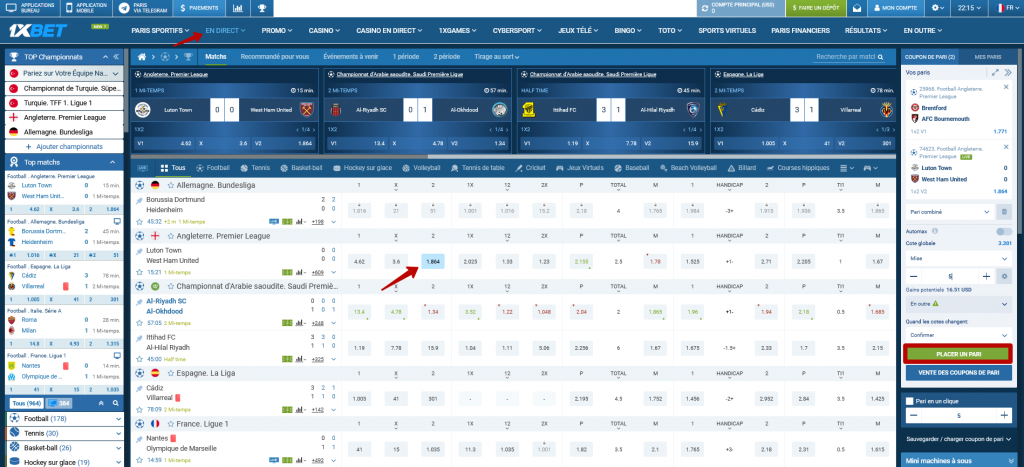

Les clients de l’opérateur peuvent placer des paris sportifs à la fois depuis des ordinateurs fixes et des appareils mobiles. Pour ce faire, ils doivent suivre quelques étapes simples :

- Se connecter sur le site ou l’application du bookmaker, s’identifier ;

- Accéder à la ligne de paris avant-match et en direct – choisir la discipline et le match ;

- Cliquer sur la cote du résultat prévu du match – un coupon sera automatiquement créé et il sera possible de le remplir ou de continuer à sélectionner des événements pour un pari combiné ;

- Placer le montant du pari ;

- Activer un code promo si possible ;

- Enregistrer le coupon.

Une fois que tous les matchs sportifs sélectionnés par le joueur seront terminés, l’opérateur en ligne fera le bilan de la transaction et il sera alors évident dans quelle mesure le parieur a réussi à faire une prédiction exacte et précise.

Les paris sportifs express sont une option passionnante disponible. Avec 1xBet paris en ligne, les parieurs peuvent combiner plusieurs sélections dans un seul ticket de pari, ce qui permet de multiplier les gains potentiels. Que vous soyez un fan de football, de tennis, de basketball, ou de tout autre sport, vous pouvez créer des accumulations de paris pour maximiser vos profits. L’interface conviviale de 1xBet facilite la construction de vos paris express, et les cotes compétitives offertes par la plateforme en font une option attrayante pour les amateurs de paris sportifs.

Choix des disciplines pour les paris

Généralement, de nombreuses agences de bookmakers couvrent les principales disciplines sportives, ainsi que les matchs et championnats les plus importants dans le cadre des disciplines présentées. 1xBet n’est pas par hasard l’un des cinq meilleurs bookmakers au monde. La société propose à ses utilisateurs une gamme incroyablement large d’événements. Chaque jour, le site de l’opérateur propose des dizaines de disciplines sportives avec plus de quatre mille marchés de paris.

En pré-match et en direct, le bookmaker effectue un aperçu des événements les plus importants, ainsi que couvre même les matchs locaux dans des disciplines rares. Pour faciliter la recherche et la sélection de matchs intéressants pour le joueur, le site de la société propose des sélections des championnats et matchs phares, des matchs recommandés, des grilles de tournois et des filtres pour trier les événements. Les clients de l’opérateur en ligne peuvent parier sur les types de sports suivants :

- Disciplines populaires – football, hockey, tennis, esport, volleyball, tennis de table, basket-ball, cricket, football américain ;

- Courses automobiles, boxe, fléchettes, combats de boxe, crosse, lutte, cyclisme ;

- Baseball, water-polo, handball, snooker, natation, courses de bateaux ;

- Speedway, pesapallo, échecs, Formule 1, biathlon, ski ;

- Rugby, surf, courses de motos, football gaélique et australien, hurling, et bien plus encore.

Les cotes du bookmaker

Les cotes sont ce sur quoi il est important de se concentrer lors du choix d’un bookmaker en ligne. La société de paris 1xBet se positionne comme un opérateur offrant les cotes les plus élevées. En étudiant les offres dans la ligne de paris avant-match et en direct, on peut remarquer que le niveau des cotes proposées est effectivement beaucoup plus avantageux que celui des concurrents. 1xBet établit une marge assez basse, ce qui rend les paris sportifs avec cet opérateur avantageux.

Dans l’ensemble, la marge dans la boutique en ligne est fixée dans une fourchette de 1 à 3 %. En fonction des marchés et de l’importance des matchs, la taille de la marge chez 1xBet peut varier :

- Petits marchés et rencontres peu populaires – 6 % ;

- Petits marchés en direct – 8 %.

En ce qui concerne les cotes proposées par le bookmaker en ligne pour les différentes disciplines sportives, les indicateurs seront approximativement les suivants :

- Pour les matchs de football, la marge peut être comprise entre 2 et 3 % ;

- Pour les compétitions de basketball – entre 3 et 5 % ;

- Pour le hockey – entre 3 et 4 % ;

- Pour les rencontres de basketball – entre 3 et 5 % ;

- Pour les tournois de tennis – entre 3,5 et 5 %.

Les paris 1xBet en direct

Avec 1xBet pari en ligne, les amateurs de sport peuvent parier en temps réel sur une variété d’événements sportifs, qu’il s’agisse de matchs de football, de tennis, de basket-ball, ou d’autres sports passionnants. À cette fin, le site de la société 1-x-Bet dispose d’une section spéciale appelée « 1xBet Live », où tous les événements disponibles pour les paris en temps réel dans le monde du sport sont réunis. L’opérateur est réputé pour la plus grande variété de paris en direct. Une caractéristique spéciale de cette société est également la possibilité pour le parieur de combiner des paris en direct avec des paris avant-match dans une seule transaction.

Pour les disciplines les plus populaires, le bookmaker propose également des diffusions vidéo en direct, où le joueur peut observer toutes les actions des équipes et des participants, les commentaires et le déroulement du match dans son ensemble. Les diffusions, en général, sont disponibles pour les sports suivants :

- Football ;

- Tennis ;

- Basketball ;

- Volleyball ;

- Hockey ;

- Matchs de cyber-sport.

Pour les principaux matchs de football, il est possible de trouver plus de deux cents marchés en direct. De bonnes lignes sont également proposées pour les matchs de hockey et de basketball – jusqu’à cent marchés. En ce qui concerne les cotes en direct, les taux de marge varieront de 3 % à 5 %. Pour les disciplines sportives plus rares, on peut observer des taux de marge de 6 % à 8 %.

Accéder au site officiel 1xbet.ci

Les autorités de certains pays peuvent demander aux fournisseurs de bloquer l’accès à 1xBet. Cela est dû au fait que l’opérateur n’obtient pas de licence dans un pays spécifique, mais opère sur la base d’une licence internationale. De plus, dans certains cas, l’accès au site Web officiel de l’opérateur peut être impossible en raison de problèmes techniques, de maintenance ou de modernisation du site.

Comment accéder au site officiel 1xbet.ci ? Pour contourner le blocage, l’administration de la société a prévu des liens miroirs, qui sont essentiellement des copies exactes du site Web principal de l’entreprise. Parmi les fonctions utiles des miroirs, on peut noter l’accès alternatif au site de l’entreprise pour améliorer l’accessibilité, ainsi que la réduction du trafic réseau et de la charge sur le site officiel.

Grâce à un miroir actif, dont la liste est constamment mise à jour, les joueurs de Côte d’Ivoire peuvent accéder librement à leur compte de jeu, et les nouveaux utilisateurs peuvent s’inscrire et créer un compte. L’utilisation des miroirs facilite également la prise de paris, la gestion du compte, la participation aux jeux de casino en ligne et l’utilisation des bonus de l’opérateur. Où trouver les liens miroirs ? Il existe plusieurs options :

- Demander aux représentants du support 1xBet ;

- Utiliser les informations sur des sites spécialisés ;

- Visiter les forums où les parieurs expérimentés partagent des liens miroirs ;

- Télécharger le programme 1xBet Access.

Télécharger l’application 1xBet sur smartphone ou PC

Simplifier au maximum le processus de prise de paris sportifs est possible grâce à l’application officielle de 1xBet. La société de paris offre à ses fans une excellente opportunité d’utiliser toutes les fonctionnalités du site principal à tout moment via des smartphones et des tablettes. Développé en tenant compte des dernières tendances dans le domaine des paris mobiles, le logiciel du bookmaker permet de créer un profil et de gérer le compte personnel. Pour les amateurs de paris sur PC, l’opérateur a également créé et propose de télécharger une application distincte.

Application pour Android et iOS

La plupart des clients du club de paris utilisent leurs téléphones pour passer des paris. Conscient de cette caractéristique, le premier opérateur sportif, 1xBet, a développé et met constamment à jour son application officielle. Le programme pour les appareils mobiles est disponible en deux versions :

- Pour les smartphones et les tablettes fonctionnant sous Android ;

- Pour les appareils iOS.

Les fans de 1xBet peuvent télécharger gratuitement l’application mobile sur leur smartphone directement sur le site de l’opérateur !

Trouver l’application mobile officielle est simple, il suffit de se rendre sur le site officiel de l’entreprise et de sélectionner la section des programmes située à côté du logo. Pour installer le logiciel sur les appareils Android, le joueur doit effectuer les actions suivantes :

- Autoriser l’installation de programmes provenant de sources inconnues dans les paramètres du smartphone ;

- Accéder à la section des applications sur le site du bookmaker et cliquer sur « Android » ;

- Attendre le téléchargement du fichier 1xBet APK et l’ouvrir.

L’application officielle peut également être téléchargée facilement sur les iPhones et iPads. En fait, la société de paris propose sur son site un lien actif pour accéder à l’App Store officiel, où le téléchargement de l’application se fera selon la procédure standard :

- Sur l’App Store, à côté de l’application 1xBet, cliquer sur « Télécharger » ;

- Confirmer l’opération via Face ID ou le code d’accès ;

- Attendre que l’application soit enregistrée dans la mémoire de l’appareil.

Un grand nombre de disciplines sportives, la possibilité de parier sur des matchs sportifs à tout moment pratique, de regarder des diffusions vidéo, d’accéder aux machines à sous et aux jeux de casino en direct sont désormais disponibles aux utilisateurs grâce à l’application 1xBet. Les fans d’applications mobiles pourront apprécier la convivialité, la fonctionnalité du logiciel et la réponse rapide de chacun des éléments du menu. L’interface pratique et compréhensible permettra de facilement découvrir toutes les possibilités du programme, et la gestion du profil personnel permettra également de réaliser rapidement des transactions financières.

Client de bureau

Les développeurs de programmes n’ont pas oublié les fans de paris depuis un ordinateur de bureau. Dans une section spéciale du menu de l’opérateur en ligne, l’entreprise propose à ses clients de télécharger un client de bureau fonctionnel et facile à utiliser. Le programme, appelé 1xWin, est conçu pour les ordinateurs et les ordinateurs portables fonctionnant sous les systèmes d’exploitation Windows XP, 7, 8, 10. L’installation de l’application de 1xBet sur PC se fait gratuitement et est très simple. Pour ce faire, il suffit de :

- Sélectionner la section avec l’application 1xWin ;

- S’assurer que le logiciel correspond aux exigences du système d’exploitation utilisé ;

- Cliquer sur « Télécharger » ;

- Exécuter le fichier d’installation ;

- Suivre les instructions et attendre la fin de l’installation du logiciel.

Les joueurs réguliers et même les nouveaux clients pourront installer le client de bureau de 1xBet et s’inscrire facilement par la suite. Grâce à un logiciel pratique pour les ordinateurs, les amateurs de paris sportifs auront un accès direct et sans entrave à l’ensemble des services du bookmaker. Les joueurs auront accès aux paris avant-match et en direct, aux toto, aux machines à sous en ligne et aux jeux de casino en direct, à 1xZone, à toutes les offres et bonus actuels.

Comment utiliser 1xBet en français ?

Aujourd’hui, le premier bookmaker en ligne, 1xBet, est connu dans de nombreux pays du monde. L’opérateur titulaire d’une licence internationale offre à ses clients une utilisation maximale du site officiel. Les joueurs de Côte d’Ivoire ont accès à 1xBet en français. L’interface du site en version française permet de découvrir facilement tous les produits de la société de paris et de comprendre facilement comment placer un pari sportif.

Si après avoir accédé au site de l’opérateur, celui-ci n’est pas automatiquement traduit en français, le joueur peut toujours choisir la langue grâce à la barre appropriée située dans le coin supérieur droit. Les joueurs de Côte d’Ivoire apprécieront la transformation du site, ainsi que la convivialité de tous les éléments du menu et des boutons de navigation.

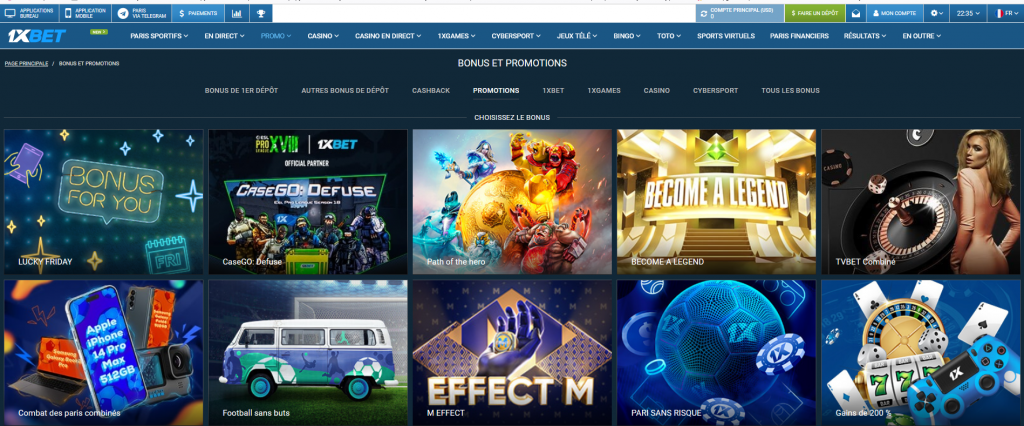

Promotions et bonus

Devenir un joueur actif enregistré chez 1xBet signifie non seulement avoir la possibilité de placer des paris sportifs dans des conditions avantageuses. Les clients de l’opérateur en ligne ont accès à des bonus généreux et des promotions alléchantes, qui couvrent les intérêts des amateurs de paris sportifs et de casinos en ligne. Sur le site, chaque personne intéressée peut découvrir toutes les promotions disponibles, mais parmi elles, les plus populaires et les plus demandées sont les suivantes:

Assurance de pari

Pour ceux qui ne sont pas sûrs de l’exactitude et de la justesse de leur prédiction, le bookmaker en ligne propose une offre intéressante appelée « Assurance de pari ». Ce service est payant, et le montant de la prime dépend du coefficient de l’issue du match/matchs choisi(s). Ce bonus peut être utilisé pour assurer des paris sportifs sous forme de paris simples ou d’express.

Le joueur peut acheter plusieurs assurances pour le même pari, à condition que le montant de l’assurance ne dépasse pas le montant de la mise elle-même. Si le pari est gagnant, le parieur recevra son gain. Si la prédiction s’avère incorrecte, la société remboursera au joueur le montant de la mise assurée. Le bonus peut être activé dans l’onglet « Historique des paris » du compte personnel.

Cadeaux pour dépôt

Après avoir utilisé le bonus de bienvenue, les cadeaux pour dépôts ne s’arrêtent pas là pour les nouveaux clients de l’entreprise 1xBet. Dans le cadre du programme de fidélité 2024, le bookmaker propose les bonus suivants pour les dépôts:

- « Vendredi Chanceux » – le vendredi, il suffit au joueur de déposer au moins 1 euro sur son compte pour que le bookmaker lui offre un bonus équivalent à 100 %. Le bonus peut être joué dans les 24 heures en plaçant des paris combinés (express) avec des coefficients à partir de 1.4.

En déposant sur son compte un vendredi et un lundi, l’opérateur en ligne 1xBet offre jusqu’à 100 euros de paris gratuits !

- « Mercredi – Multipliez par deux » – pour les participants de la promotion précédente, le bookmaker en ligne propose de multiplier à nouveau leur dépôt par 100 %. Pour cela, il faut cinq paris sur des événements avec un coefficient de 1.4 grâce aux bonus du vendredi. Ensuite, il suffit de faire un dépôt d’au moins 1 euro le lundi. Le joueur peut recevoir jusqu’à 100 euros maximum. Ce cadeau doit être joué dans les 24 heures avec une exigence de mise de 3 fois. Avec l’argent du cadeau, des express de trois matchs ou plus peuvent être constitués, avec au moins trois événements ayant un coefficient de 1.4.

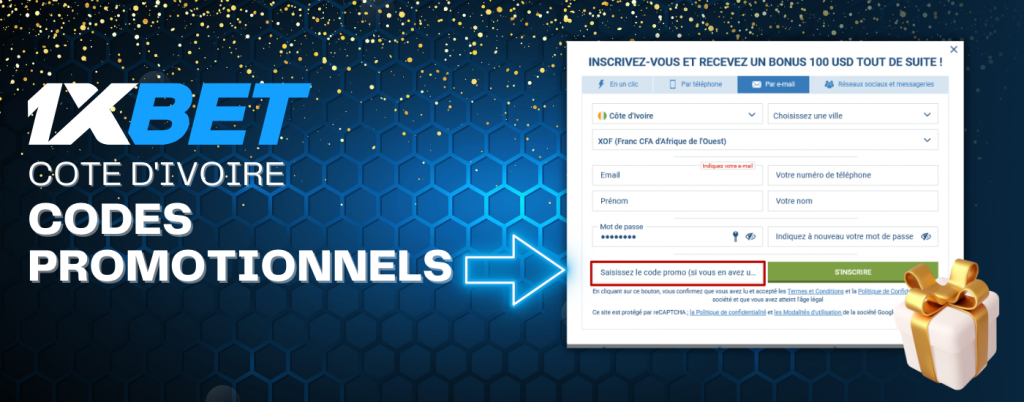

Codes promotionnels

Les codes promotionnels sont une option populaire pour les bonus dans le club de paris 1xbet.ci, qui permet d’augmenter le bonus d’inscription, les bonus de dépôt et même d’obtenir une récompense gratuite. Comment cela fonctionne-t-il ? Le joueur doit trouver ou recevoir un coupon bonus unique, qui est un ensemble de symboles (chiffres, lettres). Chaque code promo 1xBet individuel a son propre objectif. Pour les nouveaux joueurs, il y a une chance d’augmenter le bonus de bienvenue jusqu’à 130 %. Les clients réguliers peuvent activer des codes promotionnels pour obtenir un bonus de recharge, placer des paris avec des bonus et recevoir des cadeaux gratuits.

Les coupons de bonus sont une façon excitante pour les parieurs de maximiser leurs gains sur cette plateforme de paris sportifs renommée. Parmi les offres spéciales, vous trouverez le « coupon 1xBet gratuit du jour, » qui est une opportunité fantastique pour les parieurs. Chaque jour, 1xBet propose un coupon gratuit, permettant aux utilisateurs de placer des paris sans risquer leur propre argent. Ces coupons peuvent être utilisés sur une variété de sports et d’événements, offrant ainsi une chance de gagner sans dépenser. C’est l’une des nombreuses façons dont 1xBet récompense ses utilisateurs fidèles et offre une expérience de jeu enrichissante.

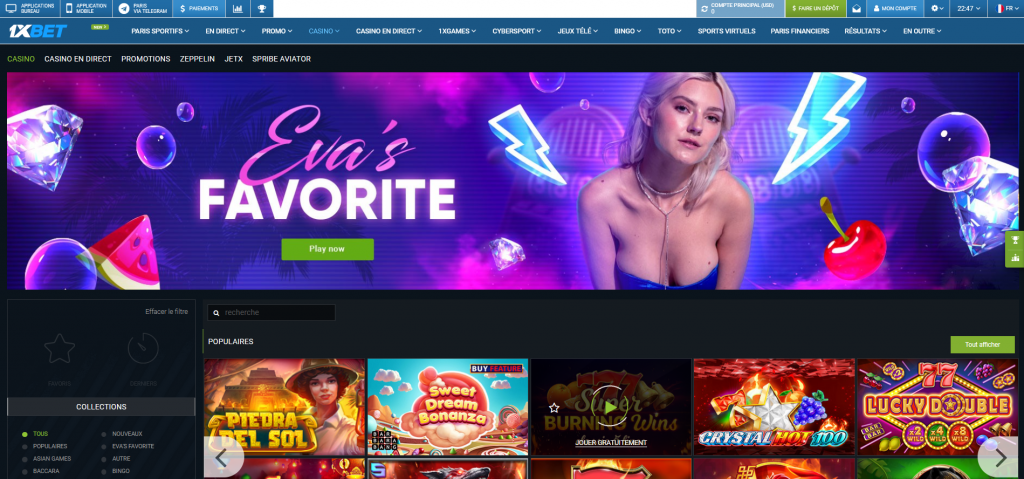

1xBet Casino et les jeux populaires

Le premier opérateur en ligne n’a pas négligé l’industrie du jeu en ligne. Les fans de machines à sous, de jeux de table, de cartes et de divertissements avec de vrais croupiers peuvent visiter le casino 1xBet. Les clients enregistrés auprès du bookmaker ont accès à différentes machines modernes et à des machines à sous vidéo, à des jeux asiatiques, à des machines à sous avec jackpot, au blackjack, au baccarat, à la roulette, au keno, au bingo et aux machines à sous en 3D. Il y a aussi une catégorie de jeux dirigés par des croupiers en direct, auxquels on peut même participer depuis des smartphones.

Le casino en ligne 1xBet collabore exclusivement avec les fournisseurs de logiciels de jeu les plus performants et éprouvés. Plus de cent vingt développeurs sont présents dans l’assortiment des divertissements du casino 1xBet. Les joueurs de hasard ont accès aux produits d’entreprises bien connues telles que Belatra Games, Endorphina, EvoPlay, PG Soft, Slot Factory, Mancala gaming, Spinomenal, Playson, 3 oaks Gaming, Mr Slotty, Betixon, etc. Les jeux les plus populaires sont considérés comme la sélection de ces machines à sous dans la catégorie éponyme :

- Book of Demi Gods

- Legend of Perseus

- Double Blazing Hot

- Hot Fruits on Fire

- Book of Games

- Wild Cash

- Sky Lantern

- It’s a Joker

- Book of Ra 6

- Solitaire.

Méthodes de dépôt et de retrait

Pour tout client enregistré auprès de la société de paris 1xbet.ci, il est facile de gérer son compte de jeu. L’opérateur en ligne a prévu une sélection de méthodes de paiement disponibles en fonction de la géolocalisation de l’utilisateur. Les joueurs de hasard de Côte d’Ivoire ont accès à diverses options pour recharger leur compte et retirer leurs gains :

| Méthode | Montant minimum de dépôt | Montant minimum de retrait | Commission | Délai de dépôt/retrait des gains |

| Visa, Mastercard | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 1-5 jours |

| Skrill | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| Neteller | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| PaySafeCard | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| ecoPayz | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| Webmoney | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| Orange money | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| Jeton Cash | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| BPay | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| Run Pay | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| PayFix | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

| Cryptocurrencies: Bitcoin, Litecoin, Doge, Ethereum, etc. | 1 EUR | 1.5 EUR | 0 % | Immédiat / 15 minutes à 24 heures |

Avis des clients sur le bookmaker

Les avis sur 1xBet.com agence de paris en ligne sont variés, reflétant l’expérience diversifiée des utilisateurs de cette plateforme de paris sportifs. Certains saluent les cotes attractives et la vaste sélection d’événements sportifs disponibles, tandis que d’autres apprécient les options de paris en direct et les jeux de casino en ligne proposés par la société. Cependant, il est important de noter que les avis peuvent varier en fonction de l’expérience personnelle de chaque utilisateur. Certains ont eu des expériences positives en matière de paris et de service client, tandis que d’autres ont soulevé des préoccupations concernant le service client ou les procédures de vérification. Il est recommandé aux nouveaux utilisateurs de faire preuve de diligence raisonnable, de lire les avis et de se familiariser avec les termes et conditions de 1xBet avant de s’engager dans des paris en ligne.

Aberash, 20 ans

J’aime parier sur les sports, surtout avec un bookmaker en ligne fiable. 1xBet fait partie de mes favoris, je fais confiance à l’entreprise et je reçois toujours mes gains.

Ada, 31 ans

Je préfère me détendre avec des machines à sous. Parfois, je place quelques paris. J’aime 1xBet car je peux être sûr de recevoir mes gains. Le bookmaker ne m’a jamais déçu.

Hiba, 40 ans

J’ai choisi cette entreprise en raison de la large couverture des paris sportifs. J’aime plusieurs disciplines, et toutes sont représentées sur le site de 1xBet. La navigation est facile, il y a des diffusions en direct et les cotes sont régulièrement mises à jour, ce qui me permet de réagir rapidement aux matchs et de prendre de bonnes décisions. Je suis satisfaite de cet opérateur et je l’ai recommandé à mes amis.

Makena, 25 ans

Après le travail, j’aime me détendre en jouant aux machines à sous. J’apprécie également la vaste sélection de matchs de football que j’aime beaucoup. Je place souvent des paris. 1xBet était le choix optimal car le bookmaker propose à la fois des paris sportifs et un casino avec une excellente collection de machines à sous.

Imani, 34 ans

Je suis un fan de paris sportifs, donc je juge les offres des bookmakers de manière exigeante. 1xBet m’a plu avec son site convivial, sa large couverture et ses cotes assez avantageuses. Je tiens également à souligner les applications pour smartphones, qui peuvent être téléchargées gratuitement et qui me tiennent informé de tous les événements.

Masego, 40 ans

Avec des amis, nous sommes devenus accros à 1xBet depuis environ un an. Excellent bookmaker avec des cotes élevées. J’aime le Toto et les promotions régulières pour les dépôts.

Nala, 28 ans

Je place souvent des paris sportifs, en particulier sur les matchs de football. 1xBet accorde une grande attention au football, offrant une large gamme de marchés et une cote variée. Grâce aux bonus, les paris sportifs me rapportent encore plus de profits que je n’aurais pu l’espérer.

Ola, 36 ans

Après une semaine de travail, je me fais plaisir en plaçant des paris sportifs sur 1xBet. C’est une excellente entreprise, honnête, avec des bonus avantageux.

Zendaya, 27 ans

Je soutiens quelques équipes de football, donc lorsque le bookmaker couvre leurs matchs, j’essaie toujours de placer des paris. J’aime 1xBet pour sa large couverture, ses cotes détaillées et ses bonus avantageux. On peut souvent placer des paris avec des codes promotionnels. C’est un opérateur vérifié et fiable. Je le recommande.

Idir, 19 ans

Le bookmaker est vraiment bon, avec de nombreuses promotions et une large couverture des matchs. J’aime particulièrement le basket-ball, et l’opérateur propose toujours des options intéressantes et des cotes élevées.

Contacts du service d’assistance aux joueurs

Le principal opérateur sportif en ligne, 1 x Bet, assure une assistance constante à ses clients 24 heures sur 24. Les utilisateurs de la maison de paris peuvent à tout moment contacter le service d’assistance technique pour résoudre les questions les plus importantes et même obtenir des consultations en ligne. Les joueurs de jeux de hasard font souvent appel au support pour les raisons suivantes :

- Le joueur a oublié son mot de passe du compte.

- Problèmes de retrait d’argent.

- Le compte du joueur est bloqué.

- Questions concernant l’utilisation des bonus.

Pour ses fans, 1xBet bookmaker fournit un numéro de téléphone pour la ligne d’assistance, un formulaire de contact, un chat en direct, ainsi que les adresses e-mail suivantes pour contacter le service d’assistance technique :

| Service | |

| Support technique | [email protected] |

| Sécurité de l’entreprise 1xBet | [email protected] |

| Relations publiques et publicité | [email protected] |

| Service partenaires | [email protected] |

| Questions financières | [email protected] |

| Représentant de la sécurité de l’information | [email protected] |

| Représentant de la confidentialité | [email protected] |

| Questions générales | [email protected] |

Réponses aux questions fréquentes

🤔 Qui peut devenir client de l’opérateur sportif 1xBet ?

Pour devenir un utilisateur enregistré de 1xBet Côte d’Ivoire, vous devez être majeur.

🔍 Comment s’inscrire auprès du bookmaker 1xBet ?

L’opérateur en ligne propose quatre options d’inscription au choix : en un clic, par numéro de téléphone mobile, via un compte de réseau social ou une adresse électronique.

🎁 Quel bonus de bienvenue 1xBet peuvent recevoir les joueurs de Côte d’Ivoire ?

La société de paris offre aux nouveaux joueurs un bonus de 100% sur leur premier dépôt à partir de 1 euro, pouvant atteindre 60 000 XOF sur le premier dépôt.

📱 Peut-on placer des paris sportifs sur 1xBet Cote d’Ivoire depuis un téléphone ?

Oui, l’entreprise de paris propose à ses clients une version mobile du site officiel et des applications propriétaires qui fonctionnent sur les appareils Android, iPhone et les ordinateurs de bureau.

📍 Où trouver l’application mobile 1xBet ?

Les logiciels propriétaires sont disponibles en libre accès sur le site officiel du bookmaker.

💸 Faut-il payer pour télécharger l’application mobile 1xBet ?

Non, tout le monde peut télécharger gratuitement le logiciel propriétaire de 1xBet.

🔒 Que doit faire un joueur si l’accès au site 1xBet est bloqué ?

Pour contourner les blocages, l’opérateur fournit régulièrement à ses clients des miroirs actuels. L’accès aux produits du bookmaker est également possible via le client de bureau et l’application mobile propriétaire.

🏟️ Comment parier sur 1xBet ?

Placer un pari est très simple – le joueur doit choisir une discipline sportive, un événement spécifique et cliquer sur le coefficient. Un coupon sera automatiquement créé, puis des événements supplémentaires peuvent être ajoutés pour composer des accumulés, des systèmes, des chaines.

🎰 Peut-on jouer à des jeux de casino en ligne sur 1xBet ?

Oui, les clients de l’opérateur peuvent visiter le Casino 1xBet et lancer n’importe quelle machine à sous, jeu de table ou de cartes.

💰 Quels bonus l’opérateur en ligne 1xBet offre-t-il pour les dépôts ?

Les clients de l’opérateur peuvent recevoir un bonus de 100% sur les dépôts effectués le vendredi et le mercredi.

🔐 Comment puis-je m’autoriser à accéder à mon compte 1xBet ?

Pour se connecter à mon compte 1xbet, suivez ces étapes simples. Rendez-vous sur le site Web de 1xBet et cliquez sur le bouton « Connexion » en haut à droite de la page d’accueil. Saisissez votre nom d’utilisateur et votre mot de passe dans les champs correspondants. Assurez-vous que les informations sont correctes, puis appuyez sur le bouton « Connexion ».

👍 Comment puis-je obtenir un coupon 1xbet gratuit pour des paris ?

Pour obtenir un coupon 1xbet gratuit pour des paris, vous devez généralement participer aux promotions et aux offres spéciales proposées par 1xBet. Ces promotions peuvent varier en fonction de l’événement sportif en cours ou d’autres occasions spéciales. Il est recommandé de consulter régulièrement la section « Promotions » sur le site Web de 1xBet pour découvrir les offres en cours.

🏆 Comment gagner sur 1xBet ?

Gagner sur 1xBet nécessite de la prudence, de la recherche et de la gestion judicieuse de vos paris. Tout d’abord, il est essentiel de suivre de près les événements sportifs et de faire des recherches pour prendre des décisions éclairées. Utilisez les statistiques, les analyses et les conseils d’experts disponibles sur la plateforme.

🎁 Comment parier gratuitement sur 1xBet ?

Pour parier gratuitement sur 1xbet, vous pouvez profiter des offres promotionnelles et des bonus offerts par la plateforme. Gardez un œil sur les promotions en cours, telles que les coupons gratuits du jour, les paris gratuits pour les nouveaux utilisateurs, ou les bonus. Ces offres peuvent vous permettre de placer des paris sans risquer votre propre argent.